When factory-finished floors first appeared in the U.S. hardwood flooring market, they were seen as a novelty. Back in the early days, there were only a handful of factory-finished flooring manufacturers and products available, and few homes had the flooring installed. But times have changed, and the hardwood flooring market has reflected changes in American culture. Today, consumers want choices and convenience, and factoryfinished flooring meets those demands. As a result, the factory-finished market has proliferated into a booming market with a multitude of manufacturers offering a vast array of colors, styles and sizes. Over the past half-century, factory-finished flooring has evolved from its modest beginnings to a major market force. Following are highlights from along the way.

1940s and 1950s: Factory Finishing Begins

During World War II, Denim Springs, La.-based Higgins Lumber Company made Navy boats out of oak plywood, and it was looking for a way to utilize the wood waste. "Mr. Higgins started looking at the waste he had and started cutting those blocks in 12-by-12s and 9-by-9s," says Warner Tweed, a retired industry veteran who now works part time with Dallas-based Trinity Hardwood Distributors. Higgins started manufacturing the unfinished blocks, and eventually the company installed a finishing line to coat them with a wax finish. At the time, the government had tight constraints on raw material and set the prices that manufacturers could charge for them. To get around this, a few wood flooring manufacturers applied finish to the wood so it became a finished product and therefore free of government restrictions.

After the war, the U.S. economy moved from war production to domestic building. Manufacturers had to find new markets for their products, and a few found them in factory-finished wood flooring. One was Memphis, Tenn.based E.L. Bruce Company. In addition to solid products, Bruce produced a 9-by-9-inch, 1/2 -inch-thick three-ply laminated (now called engineered) wax-finished parquet. The post-war military housing boom was partly responsible for developing factory-finished flooring. "The 9-by-9 laminated block was specifically designed for military housing," says Neil Moss, retired and formerly with Lancaster, Pa.-based Armstrong Hardwood Flooring. Up until the 1960s, Federal Housing Administration (FHA) rules stated that homeowners could finance only materials that would last the lifetime of the mortgage, and wood flooring was one of the few floor coverings that filled the requirement. Laminated block made for a quick and easy installation and could be installed directly over a slab.

Other large companies such as Memphis, Tenn.-based Memphis Hardwood; Warren, Ark.-based Sykes and Oneida, Tenn.-based Hartco also were major players in factory-finished flooring around this time. Hartco introduced a 6-by-6, 5/16 -inch parquet with a urethane finish, which was the first of its time. The South Carolina-based company Cloud Brothers soon followed with a urethane block. The ability of glue-down parquets to be installed directly to the slab also helped them expand into larger markets. "There are millions of feet of it installed in high-rises in New York, Chicago—the big cities around the country," Tweed says. "That's really how parquet block got started." As more metropolitan high rises continued to be built, sound control requirements became a concern, and glue-down products were able to meet the requirements. The first factory-finished floors featured heavy bevels and were produced in just a few standard sizes. Most of the products were oak, and only a couple of stain colors were available.

The early waxing process on the finishing line.

The early waxing process on the finishing line.

1960s: Beyond the Basics

In 1966, the FHA changed its mortgage rules and allowed materials that wouldn't last the life of the mortgage to be financed, making it easier for consumers to choose other options for floor covering. Hardwood flooring fell out of fashion and carpeting became popular. In these tough times, hardwood flooring manufacturers tried to develop products to gain back market share. Bruce expanded its product line and developed a laminated plank in 3-, 5- and 7-inch widths. It could be glued down over concrete with asphalt-based adhesive, which was the industry standard at the time. Columbus, Ohio-based Franklin Inter national started working with Bruce to develop a new adhesive to work with the laminated plank. This solvent-based adhesive was used up until the 1990s, when it was phased out due to environmental concerns.

The factory-finished manufacturing process was quite an undertaking during this time. Manufacturing equipment for factory finishing wasn't as readily available as it is today. "It used to be in the factory-finished marketplace that you had to have a good engineering staff because it was likely that you were going to build your own equipment," Moss explains. The floors were sanded several times with a three-drum sander, then dusted off with wire brushes. Many of the finish lines at the time operated on a two-pass system; a coat of stain was applied, and after it dried, it was sent back through the line to receive one or two coats of wax finish, either with rollers or a curtain-coater system. Many of the finish lines at the time cured the flooring with infrared ovens. Another curing process that used a combination of steam coils and hot blowing air also was implemented on several finish lines. Throughout the decade and into the 1970s, manufacturing technology continued to improve, with advances in sanding technology, drying and tolerances.

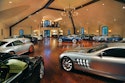

The early pressing process on factory-finished squares.

The early pressing process on factory-finished squares.

1970s: Expanding the Market

The 1970s saw many new products enter the floor covering market. Americans now demanded convenience for an increasingly busy lifestyle. "In the early 1970s when the no-wax vinyl floors came out—the designer Solariums, Congoleums, etc.— the no-wax craze hit, which moved the wood industry into thinking about putting polyurethane-type finishes on factory finishes," says Don Conner, technical product and development director at Johnson City, Tenn.-based Mullican Flooring. Consumers also wanted more options for colors, patterns and styles, and factory-finished wood flooring manufacturers increased their product offerings to cater to these trends and remain competitive. In the late 1970s, products such as planks and designer parquet patterns exploded onto the market. More engineered products also helped cater to the building boom in the Sunbelt states, where slab construction dominated. These products could be glued directly to the slab, and they were more affordable than their solid, site-finished counterparts.

Engineered factory-finished flooring was responsible for changing hardwood flooring distribution channels in the 1970s. "The products that really put factory-finished on the marketplace were the 5/16 parquet. Those were the products that changed the whole industry," Moss says. Instead of targeting the building subcontractors, large manufacturers such as Bruce, Harris, Hartco and Sykes began to sell their products directly to consumers through retail outlets. Stores such as Color Tile began displaying hardwood products alongside other floor coverings. At the time, Tommy Maxwell, now president of Monticello, Ark.-based Maxwell Hardwood Flooring, was working for Sykes, which was one of the factory-finished manufacturers having great success moving its products through these outlets. "We sold huge volumes of parquet. We sold it just like a tile to consumers," Maxwell says. Soon, more manufacturers began to take notice. "One thing led to another, and they developed marketing tools, displays and sales pieces and all the other tools to go with it," Maxwell adds. Factoryfinished parquet also began appearing in major DIY outlets that preceded the big-boxes of today. Installers and do-it-yourselfers were able to install the products quickly and easily.

Grading and packing stained and waxed factory-finished floors.

Grading and packing stained and waxed factory-finished floors.

1980s: New Style, New Technology

While cell phones, computers and fax machines were changing the way Americans did business in the 1980s, new technology in flooring manufacturing was changing the factory-finished market. European technology was influencing the U.S. market; companies such as Kährs, Tarkett and Boen were using a UVroller-coating process. Up until the 1980s, the dominant finishes were wax or solvent-based urethanes. Finishes were cured with heat by either the steam-coil system or infrared ovens. During the middle to late part of the decade, these systems began to be replaced by UV-cured urethanes, which are still the standard today. Once exposed to UV light, the finishes cure instantly. This had a huge impact on the manufacturing process; manufacturers could speed up production time, reduce the amount of space needed to produce the flooring, and apply several coats of finish. More coats of finish meant surfaces were more durable than the old stain-and-wax system. UV–cured finishes are 100 percent solids, and they don't evaporate into the air, so the change also helped reduce workers' exposure to VOCs.

Along with UV technology, Europeans also introduced longstrip and floating floor systems. As the remodeling market began to expand, these products allowed wood flooring to be installed in more homes. Hardwood flooring could now go over surfaces like vinyl or lightweight concrete, or it could be installed where solid products couldn't, such as below grade or in other high-moisture situations. "Factory-finished engineered has been the biggest driving force of them all—it really helped expand the market," says Rick Jones, director of technical services for Virginia Beach, Va.-based Scandian Inc.

Another process that helped expand factory-finished flooring's reach was acrylic impregnation, which fills the wood's cells with a plastic substance. The plastic supports the cell wall and makes the wood flooring harder and more dent-resistant. Originally designed for commercial applications, acrylic impregnation has expanded into the residential market.

Styles were changing, too. Heavily beveled parquet was falling out of fashion, and consumers wanted a cleaner, smoother look. Europeans also brought over square-edged products that were much flatter than traditional factory-finished products. "In the 1980s, all this development went on, and you got into microbevels because sanding technology and equipment came on the line to better sand the floors," Conner says. In addition to microbevels, the white floor craze also hit the market, and manufacturers mimicked what high-end contractors were doing on the job site with unfinished floors.

1990s: More Technology, More Marketing

The technology boom continued into the 1990s. The problem with white floors was that dirt got into the grain, and it couldn't be hidden with the white finish. Filling the sur face by hand with a matching fill color solved the problem, but it was laborintensive. In 1990, Clinton, S.C.-based Anderson Hardwood Floors developed a reverse fill machine that filled the grain on the surface of the wood with a clear protective coat. "The advantage of the clear was that it could be dried on the finish line," says Don Finkell, CEO of Anderson Hardwood Floors.

About the same time, Anderson and many other major manufacturers switched to waterborne stain and finishes. Regulations were getting tighter regarding solvent-based materials and VOC emissions, the environmental movement was growing stronger, and finish manufacturers were developing technology to bring waterborne products online to replace their solvent-based counterparts.

While various European products influenced the factory-finished market in the 1980s, the one import that shook the industry in the 1990s was Pergo and other laminate flooring products. These products led the wood flooring industry to adopt the term "engineered" for what was previously known as "laminated" floors. The laminate floors had a wood-like appearance and mineral-based finish that was more durable than the finish being used on wood flooring. Wood flooring manufacturers soon began testing aluminum oxide and other mineralbased finishes on their own products. In 1997, Anderson debuted its first aluminum-oxide finished flooring. By the end of the decade, most major manufacturers offered a mineral-basedfinish product. Then, Wausau, Wis.-based Award Harwood Floors came out with a product that had fine mineral particles in the topcoat, which made the surface scratch-resistant. Other manufacturers soon followed suit, and now most also have scratch-resistant coatings.

With all the new technology came new catch phrases and new ways to market factory-finished products. The more durable surface finishes led to finish warranties of 25 years and longer. The market was getting bigger, and increasingly savvy consumers had more choices. Well-designed product displays and marketing materials had to catch a busy consumer's attention. The Internet also made these consumers more informed about product choices than ever before.

2000s and Beyond: Vast Choices

The flood of products and manufacturers has continued into the new millennium. Consumers can get a factory-finished floor in almost any color and choose from a plethora of domestic and imported species. Accessories such as borders, medallions, moldings and vents for factory-finished floors have allowed consumers and installers to get more creative in their installations. There has also been an influx of overseas manufacturers, especially from China.

The construction boom in recent years has also helped fuel the growth of factory-finished flooring. Wood is being installed in more rooms in the house, and the square footage of houses is increasing. Builders on tight schedules like the floors because they require less time than site-finished wood flooring. Remodelers prefer them for their ease of installation and ability to move back onto the floors upon installation. The growth of big-box stores has helped get the products in the hands of more consumers.

While the wood flooring industry is growing as a whole, one of the fastest-growing segments is in factory-finished engineered products. "While the market has grown much larger, the biggest change in that pie has been the growth of the engineered market up against the solid market," Moss says.

Fashion trends have also changed in the 2000s. Instead of having the smooth and shiny look that became popular in the 1980s, wood floors are now low-sheen and textured. "I think there was a counter-movement in wood. People thought if they were paying extra for wood, they didn't want it confused with laminate," Finkell says. Heavy bevels and rustic-looking flooring were made popular by flooring contractors early in the decade, and as soon as the trend became more widespread, manufacturers started replicating the look in the factory.

As the market moves closer to the next decade, most industry experts see factory-finished floors continuing to gain popularity. What started out as a novelty item back in the 1950s has forever changed the landscape of the hardwood flooring market. As technological advancements continue and manufacturers find ways to meet the needs of consumers, factory-finished flooring will doubtless continue its evolution through the next 50 years.